By Shalin Hai-Jew, Instructional Designer at K-State

Colleague 2 Colleague (C2C) SIDLIT

Aug. 2 - 3, 2012

Study guides are common features of science-based (and some social science) courses. These are information sets created by learners to help them prepare for upcoming exams. If effectively designed (by the faculty member usually) and executed (by the learners) with faculty oversight, such study guides offer effective notes for student learning. They serve as powerful resources to enhance memory. Study guides are effective because they help learners synthesize (sometimes contradictory) information from various information sources and are expressed in the learners' own words to enable instructor evaluation of their actual comprehension. These guides enhance learner citations of research sources. Such digital study guides may integrate text, imagery, URLs, and other resources. These help learners take ownership of the learning and help them express their understandings through their own interpretive lenses. This presentation will include some live examples of study guides and their various strengths and weaknesses. There will be ideas for how to take the "retro" concept of a study guide and re-make study guides into interactive learning resources, with special strengths in intensive, concentrated, or accelerated courses.

Overview

"Retro" Study Guides

Contemporary Study Guides for Online Learning

Example 1: Intro to Public Health

Example 2: K-State Hale Library's Customized Study Guides

Example 3: Bridge to Success / OER (Open Educational Resources) Resources

Steps to Building Effective Study Guides for Online Learning and Assessment

Traditional study guides were created to enhance learning by highlighting the main ideas from a complex curriculum to enable learners to focus on the critical takeaways from a lesson. Instructors would often embed learning strategies with their study guides. Studies guides often expressed pedagogical strategies. They reinforced the critical learning. Often, they reduced learner anxieties and lightened cognitive loads for learners by further scaffolding the learning.

Often, study guides were created by third-party content creators / publishers who wrote textbooks, and study guides not only enhanced learner access to the materials, but these also were used by instructors as lesson planners.

Most traditional study guides were strictly "templated" with the following features:

A Traditional Study Guide Template (downloadable)

Some included sidebars or "boxes" with examples. Others included pull-outs of main points in the margins. Many study guides of old looked a lot like print chapters or excerpts of such chapters. Essentially, these showed a structuring of information. Some study guides look like actual chapters in books and may have been used that way.

Some study guides are merely a list of questions. These may include critical thinking questions.

Others are incomplete notes, with an incomplete outline of the instructor's lectures with fill-in-the-blanks work for learners. (These were popular in face-to-face large lecture courses, especially in survey courses.)

Most traditional study guides have pre-determined answers. Some instructors made these completed or filled-in study guides available to students later on. (Most of these were used for convergent learning. Convergent learning involves established understandings and facts that are generally memorized.)

A review of the literature on study guides did not result in many resources. What this review did surface were various study guides that have been archived now as .pdfs.

Independent learning in various unique contexts. Various rationales were identified for why study guides should be used. In one 90-module 12-week course covering the biological sciences for nurses, study guides were used as part of a learning lab kit including audio tapes (with "narration of the subject matter and cues for student responses"), slides, films, anatomical charts and specimens (Mentzer & Scuglia, 1975). The study guides provided "objectives for student responses" (p. 358). This learning was self-paced, and the nurses could take an objective test at the end of the time period to test their knowledge and skills. It would seem that this training could be done while nurses continued their professions in their respective and unique circumstances.

Enhancing reading comprehension. For one researcher, study guides were used to enhance learner reading comprehension (Tutolo, 1977). In light of what is known today about reading disabilities, dyslexia, and other symbolic processing and reasoning challenges, this rationale is still relevant. This author differentiated between "interlocking" and non-interlocking" types of study guides, with the first "keyed to the textbook" based on defined learning objectives, and the other more free-form (Tutolo, 1977, p. 503). The study guide was built on the assumption that "comprehension will be enhanced when directions which stipulate goals are in close proximity to the textual material containing the relevant information" (p. 504). In other words, instructors could individualize the instruction and highlight what they see as relevant. The interlocking method focused on three levels of reading: first at the level of literal meanings, then at the more analytical levels of interpretive and applicative meanings. These even involved the analysis of paragraph patterns. By contrast, the noninterlocking study guide does not create a hierarchy of reading and analysis but rather uses a more creative approach built around whatever would enhance the learning.

Adapting mass media contents for the classroom. Yet another example involved the adaptation of feature-length films and other mass media contents to have learning value in a classroom (Briley, 1998). This strategy has been applied to historical literature, too, which may need updating for relevance to a modern mind set and readership. Another work mentioned the application of a moral reasoning model to adolescent literature, using the model as an overlay. This model enabled discussion of various literary plots across multiple works using the moral reasoning model and the study guides as bridges.

Here, the study guide served as a bridge between the learners to the learning contents that were designed for another (entertainment) purpose. This could re-frame experiences. This guide could adapt a work for user use. It enabled a leveraging of outside contents.

Enhancing real-world understandings. Some study guides intersperse scientific or medical information with real-world vignettes that humanize the facts. Some study guides used case studies and scenarios (the first factual, the latter potentially fictional and based on imagination mixed with facts) to enhance the learning to be more complex, real-world, and transferable (and applied).

Briley, R.F. (1998, May). The study guide Amistad: a lasting legacy. The History Teacher: 31(3), 390 - 394. Society for History Education.

Mentzer, D.S. & Scuglia, R.C. (1975, Sept.) Teaching life science to student nurses: a modular approach. The American Biology Teacher: 37(6), 358 - 360. The University of California Press. National Association of Biology Teachers.

Tutolo, D.J. (1977, Mar.) The study guide: Types, purpose and value. Journal of Reading: 20(6), 503 - 507. International Reading Association.

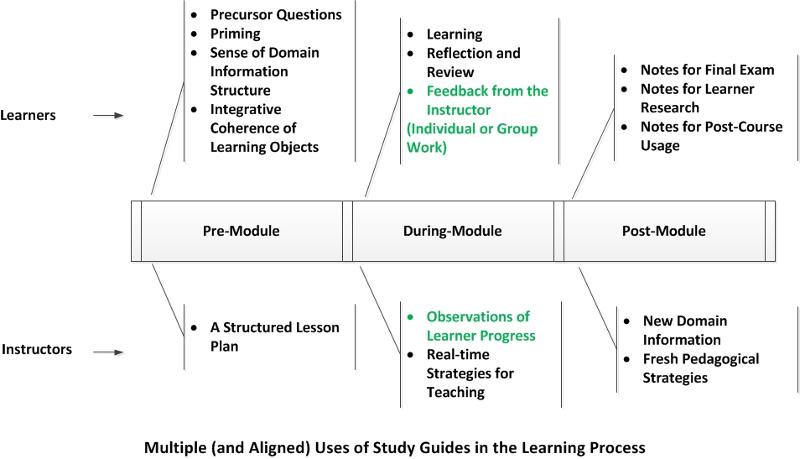

Well-designed study guides have learning value for both learners and instructors.

For a learner, a study guide lightens the cognitive load of acquiring the learning. It informs their naïve mental models with the more complex conceptual models of the subject matter experts (SMEs).

For an instructor, using study guides may result in better prepared students. Further, reviewing the study guides for the instructor may provide a sense of what is being communicated through the course lectures and study materials. These insights may help in the fine-tuning of emphasis and focus in the class.

Figure 1. Multiple (and Aligned) Uses of Study Guides in the Learning Process