People come together around homophily or shared likenesses. People of a kind will cluster. People also cluster around shared interests.This is especially true if they connected along multiple dimensions or variables.

For strategic reasons, people may cluster in heterophilous ways, too, such as colleagues from different disciplines who collaborate around a shared project. The concept of "opposites attract" may be another form of heterophily. Indeed, people interact around patterns of differential association.

Geographical or spatial proximity matters. It affects those who will collaborate in a workplace (those within 50 feet of each other's offices). It affects who people date and marry.

An average North American supposedly has 1,500 informal ties. Of these, 20 are to significant individuals in terms of sociable contacts. Of the strong ties, only 4-7 are considered intimates (Walker, Wasserman, & Wellman, 1994).

In socio-technical spaces, people may have many "friends," but many of the same patterns of connectivity applies. Many online relationships are about influence through communications, with the collection of "followers" around opinion leaders. (Influence, of course, may be direct or indirect. With the sharing of information, indirect influences may activate individuals widely. One example of this may be seen in popular culture, with such "soft power" disseminating ideas and practices and styles widely.) Most relationships last about three years among online friends, and then unfriending and unfollowing set in.

Some researchers have expressed concerns about the research done on social networks since the nodes represent individuals, who are often identified or identifiable. There are debates about how much privacy protections need to be in place. [See Charles Kadushin's "Who benefits from network analysis: Ethics of social network research" (2005) in Social Networks: 27(2005), 139 - 153.] De-identified data about individuals often may be re-identified with a few data points (and access to other related databases), so researchers have to use due care.

Mediated Friendships

People's digital trails may be analyzed to understand patterns in human relationships. The closest ties are those which are both reciprocated and active.

Most people can only manage a hand full of close friends. The others tend to be online friends...

Males in social networks will more indiscriminately friend women who ask than females will friend unknown men.

Small World Networks / Degrees of Separation

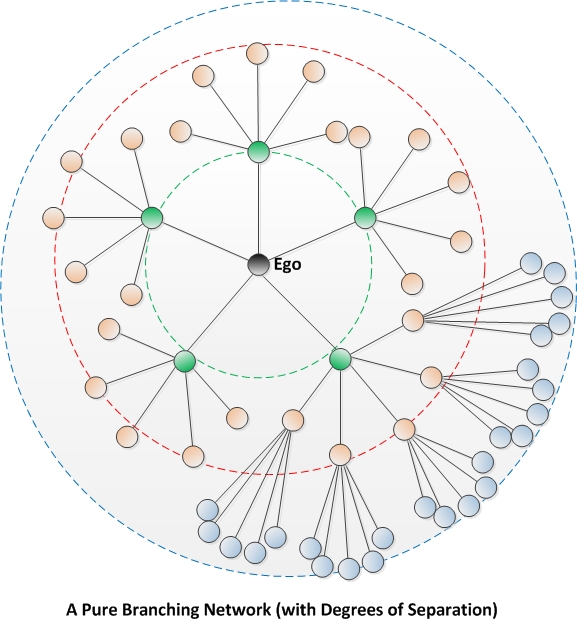

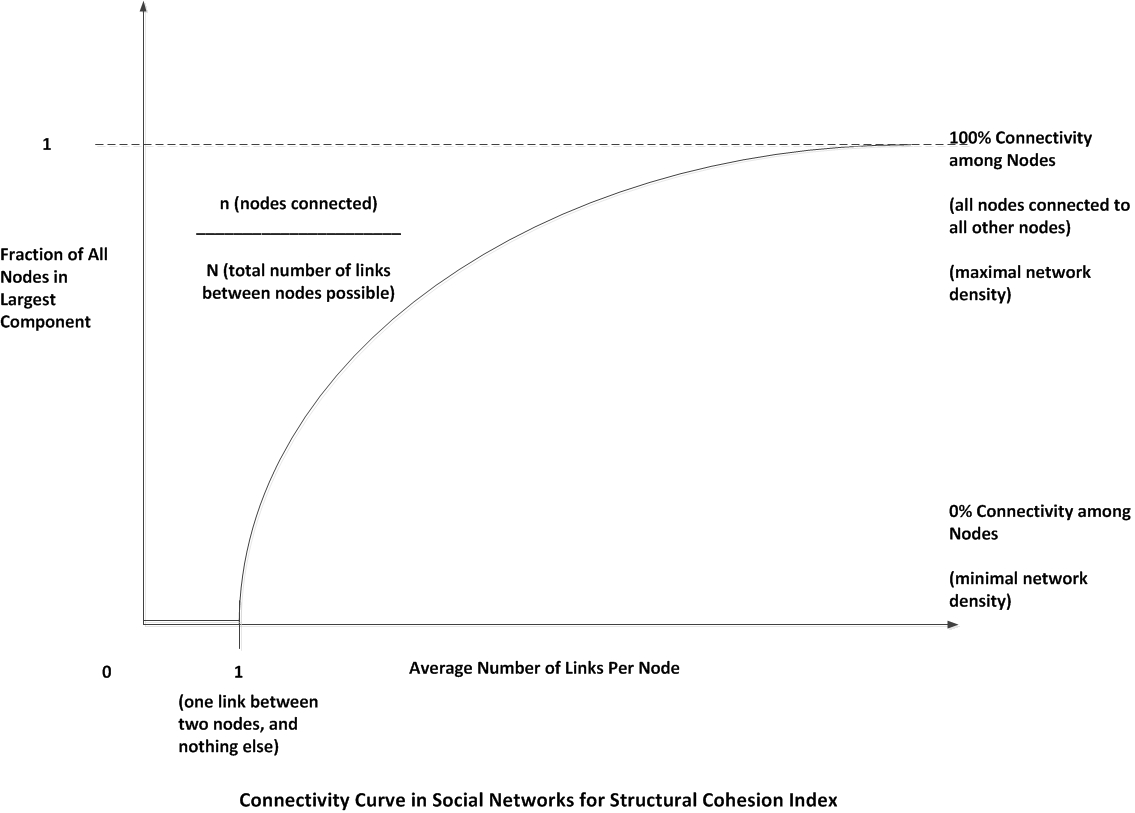

The so-called small-world networks are described as a combination of short average path lengths over the entire graph combined with a strong degree of clustering or cliquish local neighborhoods that have evolved independently in large networks.

A pure branching network is perfect balance and numbers of connections and nodes. In the real world, real networks are not based on randomness but on human tendencies to connect in preferential ways. That selectivity affects the types of intimacies that people create. This is why social networks show patterns of differential association.

The more connections there are, the more ways there are for people to connect to socialize and problem-solve. Denser networks can disseminate all sorts of exchangeable elements, some positive and some negative contagions, too.

Job Hunting and Weak Ties

Sometimes, social network research results in some counter-intuitive findings. For job hunting, the weak ties in one's circles are better than strong ties. The reason is that one already has access to the resources of the strong ties. Those who are bridges to other communities multiply the power of connectivity.

References

Walker, M.E., Wasserman, S., & Wellman. (1994). "Statistical Models for Social Support Networks." In Stanley Wasserman and Joseph Galaskiewicz's Advances in Social Network Analysis: Research in the Social and Behavioral Sciences. Thousand Oaks: Sage Publications. 64.

|

Let's Talk!

|