Some Lessons in Power

Selectorate Theory

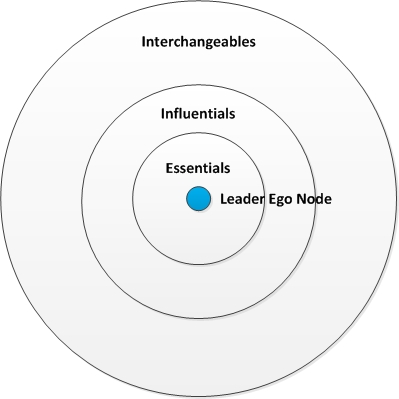

Drs. Bruce Bueno de Mesquita and Alastair Smith describe "selectorate theory" in political science which suggests that countries' leaders tend to use a very basic power equation in their governance that is all about protecting their own power by rewarding those whom they need to stay in power. Their book is about ways to structure governance to make leaders more responsible for a broader constituency in order to encourage more responsible and ethical government. At the heart of their argument lies a social network concept that is very similar to the core, semi-periphery, and periphery of a social network. Those in the periphery are the dispossessed masses (the "interchangeables") whose concerns are not considered by many government leaders. Those in the inner core are the "essentials"; in the semi-periphery are the "influentials," and on the peripheral outside are the "interchangeables".

Reference

Bueno de Mesquita, B. & Smith, A. (2011). The Dictator's Handbook: Why Bad Behavior is Almost Always Good Politics. New York: Perseus Books.

Brokerage Roles / Tertius Gaudens ("the third who benefits") / Exploiting Structural Holes

Brokerage Roles

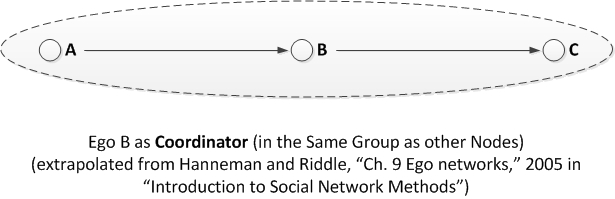

Coordinator

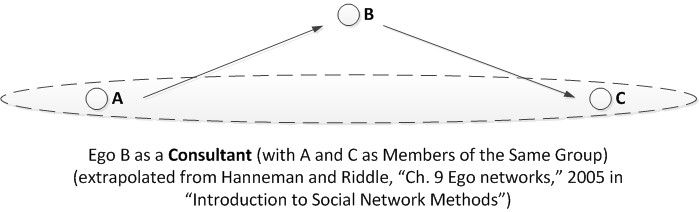

Consultant (or "itinerant broker")

or "itinerant broker" (de Nooy, Mrvar, & Batagelj, 2005 / 2011, pp. 174 - 174)

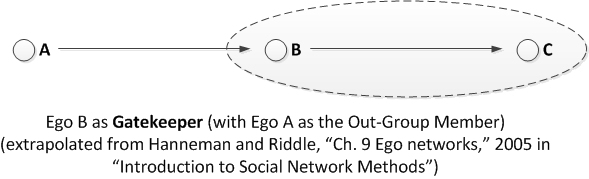

Gatekeeper

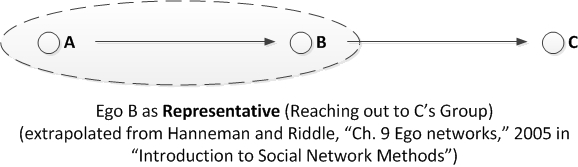

Representative

If in an undirected network, gatekeepers and representatives fit in the same category.

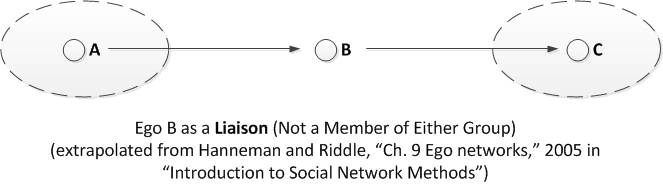

Liaison

In these brokerage roles, power derives from relationships and access to resources. Further, how a node / agent / vertex plays out the power relationships affects the outcomes.

What Brokerage Tells Analysts about a Social Network

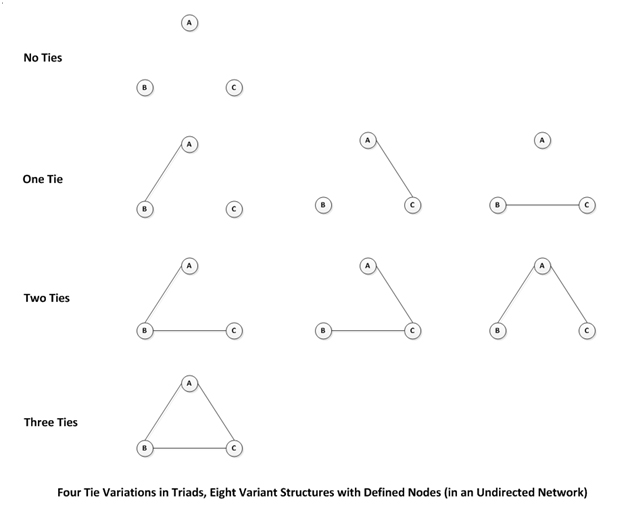

The various software programs have algorithms to search out the various types of brokerage ties to understand the overall nature of a social network. There are various types of social networks. Those that have lines without arrows are known as undirected networks. Those that have arrows on the lines are considered directed networks or directed graphs (or "digraphs").

The various types of relationships are defined as well. An "isolate" is a node that is not connected to anything. A "pendant" is a node that dangles on the edge of a network with maybe only one connection. A thin node is one with a few connections. A fat node has many incoming connections (with resources coming in), but fewer nodes going out (suggesting that a lot of the resources stay with that node). In social networks, popular fat nodes have more incoming attention (like followers in a social network) and less out-going. The "in-degree" for fat nodes are higher than the "out-degree." Some theorists assert that in preferential attachment models, nodes prefer to link to vertices with higher in-degree (e.g., popularity).

An island is a sub-network or subcluster of nodes that are densely connected with each other but less densely connected with the larger networks.

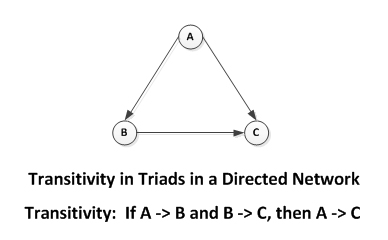

Further, there are many theories of network types (balanced networks, cyclic and acyclic networks, hierarchical vs. distributed ones, high transitivity to low transitivity ones), but very few real-world social networks conform perfectly to the theories.

A wholly hierarchical network only has information moving up, none coming down with all resources accruing at the top.

Less hierarchical networks may still be ranked based on the interactions within that network. In cases where there is cyclic movement and reciprocation and clustering, those nodes are considered to be of the same social grouping or banding (in a hierarchy).

Structurally "equivalent" brokerage conditions may suggest that a particular node setup may substitute for another. This enables work-arounds in a social network that may help create resilience. (Resilience, in systems theory, includes system attributes "as diversity, ability to self-organize, system memory, hierarchical structure, feedbacks and non-linear processes" (Cumming, Barnes, Perz, Schmink, Sieving, Southworth, Binford, Holt, Stickler, & Van Holt, 2005, p. 975). These authors note that "resilience" may be understood as the amount of change that the system may undergo while maintaining its structural and functional integrity. Further, the system's ability to learn is another aspect of system resilience.

[The above image was derived from De Nooy, Mrvar, & Batagelj (2005, 2011)].

Network Censuses: The software analyzing social networks can draw out various combinations of these triad relationships in a "triad census." It can pull out hidden relationships that are not easily viewable by the human eye. There are other censuses in the software programs that enable the finding of certain "network motifs" or structures that appear in various types of social networks.

Node Analysis and Population Base Rates: The software can be used to identify different characteristics of the nodes. At minimum, an analyst may draw out base rate characteristics of a population. (A % has this characteristic. Another % has this characteristic.)

Static vs. Dynamic Depictions of Social Networks: Social networks are dynamic; they change over time. (Certain networks may have very different forms if they are going through crises or different phases of development). This reality of time-series data may be represented as time slices, or this may be seen as a dynamic animation Social networks are not static, but they may be depicted as a moment-in-time freeze-frame reality. There are ways to model dynamism in terms of how a social network evolves over time in regards to particular dimensions. Some social networks are populated with real-time data, which suggests synchronicity in the moment for "situational awareness" now.

Reference

Cumming, G.S., Barnes, G., Perz, S., Schmink, M., Sieving, K.E., Southworth, J., Binford, M., Holt, R.D., Stickler, C., & Van Holt, T. (2005). An exploratory framework for the empirical measurement of resilience. Ecosystems: 8, 975- 987. DOI: 10.1007/s10021-005-0129-z.

De Nooy, W., Mrvar, A., & Batagelj, V. (2005, 2011). Exploratory Social Network Analysis with Pajek: Structural Analysis in the Social Sciences. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Tertius Gaudens vs. Tertius Iungens

In a triad (three nodes in relation to each other), the tertius ("third who joins") strategy occurs when one player acts as a broker between two other nodes and benefits from the disunion of the two others (known as "tertius gaudens" or "the third who benefits / rejoices" per George Simmel, 1923). A common example is a seller of a product which is being bid over by two others. Tertius gaudens occurs when there is a node which can step into a structural hole at a strategic moment which allows the individual to have control over the relationship between the two actors divided by the structural hole. A key point in brokerage involves identifying such gaps and taking advantage.

A converse idea is that of tertius iungens or ("the third who joins"). In this case, the third who joins two nodes has a more positive role between the original two, by bringing nodes together for mutual benefit (not exploitation). Further, it is understood that the nodes are selfish and each working in their own best interests. The information moving among the triadic nodes may be accurate, ambiguous, inaccurate, or even distorted / manipulated.

Identifying and Exploiting Structural Holes

A structural hole occurs when two parties (nodes / egos / vertices) are separated structurally and need a third party to mediate. This may be in a case of a divorcing couple or a seller and buyer of real estate. The go-betweens in such cases may have undue power in terms of what will occur between the two nodes. (There is a motivation for the two nodes themselves to interact to limit the power of "the third who benefits," but there may be structural or personality or other reasons why that may not be possible.)

Web Logs (Blogs) /Microblogs and Polarization

Re-Tweeting (Microblogging) and Political Polarization

"When Computation met Society"

(Note: This is conducted with text analysis tools as well.)

Terror Groups and Structures

"Connecting the Dots: Tracking Two Identified Terrorists" (by Valdis Krebs in orgnet.com)

Deep analysis of the structures of terror groups--their leadership, the various functional roles, the recruitment, the funding streams, the messages and solicitations, and so on--may give those working in intelligence ways to break up the groups through removal of certain critical nodes (leaders); compromising particular individuals in the network; misinformation; and other strategies. They may find ways in to insert individuals into the network based on the organization's perceived needs and functional gaps. They may look to break down brokerage roles for the highest impacts, to weaken or dismantle or destroy the group.

Suggested Readings

For more, read Edward P. MacKerrow's "Understanding Why--Dissecting radical Islamist terrorism with agent-based simulation," (2003) in Los Alamos Science.

Also, read Rebecca Linder's "Wikis, Webs, and Networks: Creating Connections for Conflict-Prone Settings" (2006) for the Center for Strategic and International Studies (CSIS).

|

Let's Talk!

|